“A virus is a piece of bad news wrapped up in protein” – Sir Peter Medawar, 1983

I. Viral evolution & immune evasion

All viruses mutate, and they do it often—particularly those with an RNA genome—and are able to adapt to their environments through natural selection. Such genetic changes can result result in the generation of progeny mutant viruses that, for example, cannot be recognized by the immune system, are insensitive to antiviral drugs, and enhanced ability to destroy the cells they infect. Reoviruses are not an exception and, similar to influenza virus, they can alter their genetic composition through genetic drift (“mutations”) and/or genetic shift (“exchange of viral genes”).

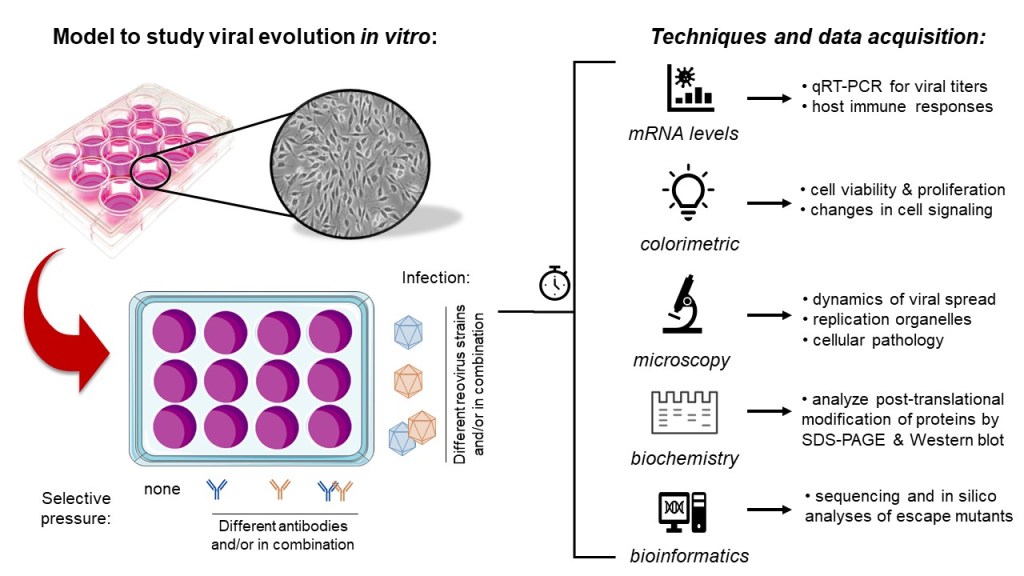

The natural evolution of reovirus has allowed different strains to interact differently with the host immune system. For example, some strains are able to antagonize immune responses in order to replicate better, while others are more efficient at infecting specific cell types. We use a combination of qualitative and quantitative tools commonly used in biomedical research including cell biology (e.g., microscopy, metabolic assays), molecular genetics (e.g., qRT-PCR, DNA sequencing, bioinformatics), and biochemistry (e.g., SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting, ectopic protein expression) to generate viruses with new properties and study their unique biology.

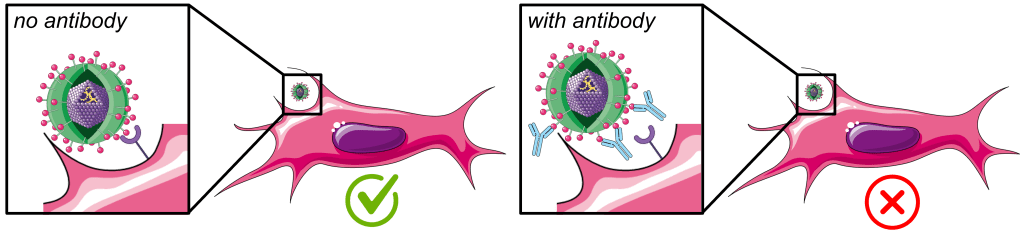

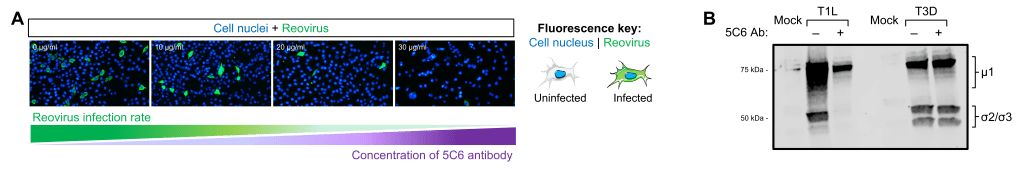

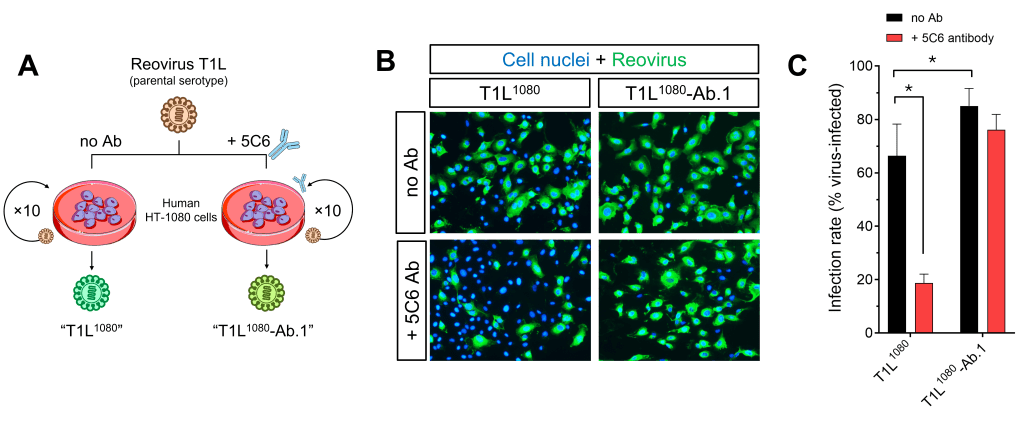

Viruses enter host cells through interactions between their attachment proteins and specific receptors on suitable host cells. One of our projects involves the infection of a mammalian cells in the presence of neutralizing antibodies against the virus attachment protein σ1 as selective pressure to better understand the flexibility and limitations of viral evolution.

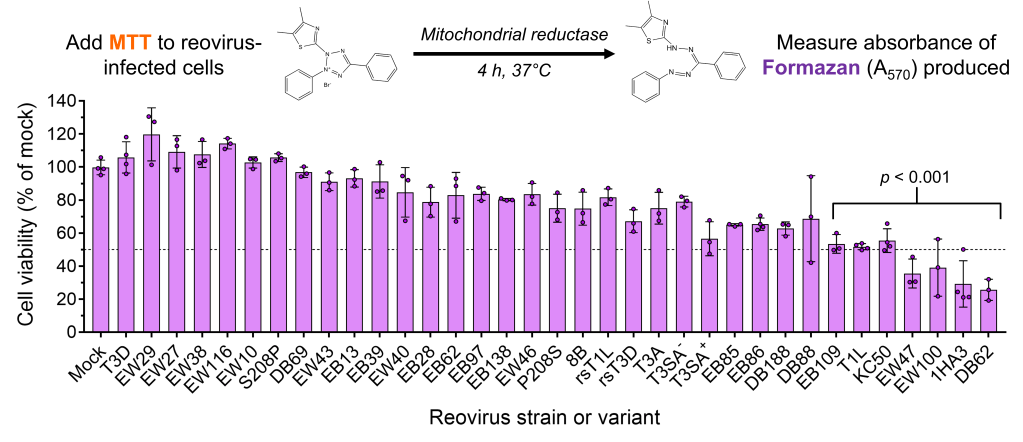

Under these conditions, only progeny virions with genetic changes that allow them to successfully escape from antibody binding are expected to survive and become the dominant variants over time through natural selection. These emerging variants can then be rescued, sequenced, and functionally characterized.

II. oncolytic virotherapy

Cancer is the second leading cause of death in the United States. This multifactorial disease occurs when cells lose their ability to regulate their cell cycle and grow out of control. Unfortunately, for most cancers we are limited to chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and/or surgery as treatment for most types of cancers, which are confounded by a lack of specificity and adverse side effects.

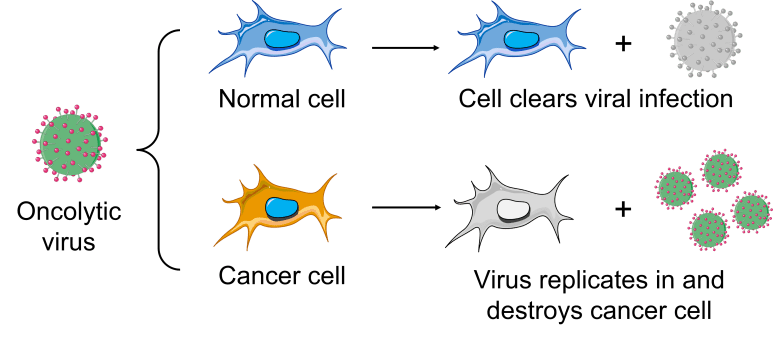

Contrary to popular belief, not all viruses are strictly associated with negative outcomes and some display features that can be beneficial to our health. For example, some viruses display selectivity for infecting and killing cancer cells—a property known as oncolytic potential—and are in clinical trials as alternatives for cancer treatment.

Our model virus, reovirus, is currently in clinical trials as mono-treatment or in combination with chemotherapy against various cancer types. Thus, we are exploring ways to direct the evolution of reovirus and generate novel variants with enhanced oncolytic properties specifically in poorly studied cancer types.

III. Cell type-specific antimicrobial responses

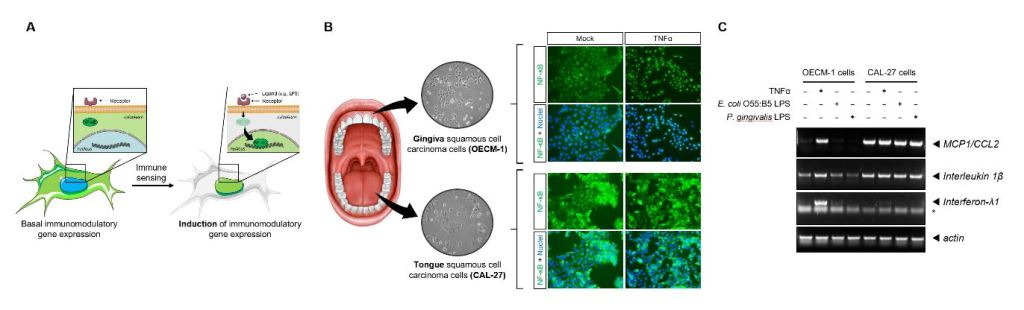

Our bodies are composed of a large number of different cell types, each with their unique physiology and ability to respond to microbial infections. We have projects studying the cell biology of viral infections in different organs—that is, how do different cell types within specific tissues (e.g., cardiomyocytes in the heart, hepatocytes in the liver, pneumocytes in the lungs, leukocytes in the blood, and others) collectively respond to viruses as foreign entities to ultimately confer antiviral protection—and how viruses quickly evolve to overcome responses exerted by our immune system.

For example, we compare how different cell types within the oral cavity differentially respond to bacterial, viral, and pro-inflammatory molecules to elicit immune responses.

IV. educational resources in virology and science communication

The limited availability of laboratory activities suitable for undergraduate courses imposes a barrier for many virology instructors across the nation. A sub-component of our research is dedicated to the design of feasible, accessible, and budget-friendly hands-on laboratories aimed at showcasing different aspects of virology principles in the classroom. Our goal is to create practical, hands-on open-access educational tools suitable for an undergraduate virology course. The current demand for such activities makes this pedagogical component of our group suitable for publication in educational journals, lab manuals, non-profit educational servers, and other online venues.

The COVID-19 pandemic was the first global infectious disease event rising in the modern age of technology, and thus exposed the power of online communication outlets as key factors shaping public health decision making and epidemiological outcomes. More notably, social media served as an accessible platform for the amplification of misinformation related to infectious diseases and vaccinology. Despite the presence of many researchers and healthcare professionals in social media platforms, their lack of training in effective communication oftentimes harmed the public’s perception and trust in science.

I strongly believe that introducing undergraduate students to effective ways of communicating science is just as important as their development in laboratory skills. Thus, a component of our research group is dedicated to the design of pedagogical activities in virology and mentoring in scientific writing.